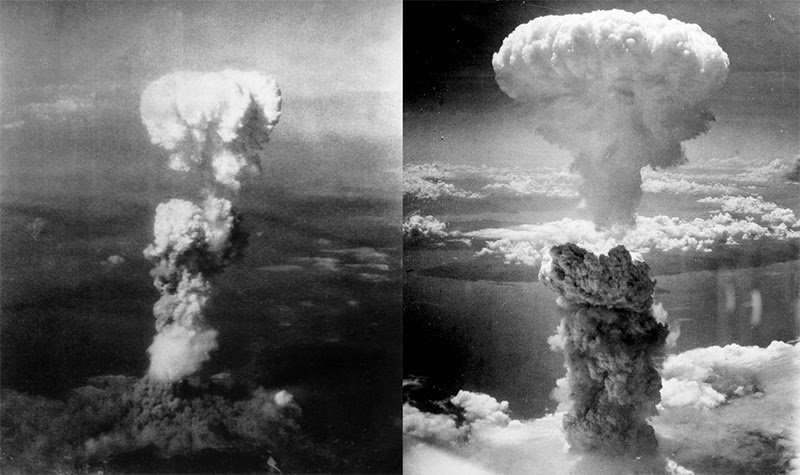

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The US dropped two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945. The bombs, which are still the only instance of nuclear weapons being used in an armed war, killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, the majority of whom were civilians. Six days after the bombing of Nagasaki, the Soviet Union’s declaration of war against Japan, and the invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria, Japan submitted to the Allies on August 15. On September 2, the Japanese government signed the surrender document, thereby bringing the war to an end.

During the last year of World War II, the Allies readied themselves for an expensive invasion of the mainland of Japan. A conventional bombing and firebombing operation that destroyed 64 Japanese cities came before this endeavor. After Germany submitted on May 8, 1945, the war in the European theater came to a conclusion, and the Allies focused entirely on the Pacific War. “Little Boy” was a fission bomb made of enriched uranium, and “Fat Man” was a nuclear weapon made of plutonium implosion. By July 1945, the Allies’ Manhattan Project had developed both types of atomic bombs. After receiving training and being outfitted with the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Silverplate variant, the 509th Composite Group of the US Army Air Forces was sent to Tinian in the Mariana Islands.

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States launched bombing strikes on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945) during World War II, which marked the first use of atomic bombs in warfare. The initial explosions claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people, while radiation poisoning claimed the lives of many more. The Japanese government announced that it would accept the terms of the Allied surrender that had been outlined in the Potsdam Declaration on August 10, one day after Nagasaki was bombed.

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Details

| Type | Nuclear bombing |

|---|---|

| Location |

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan

|

| Commanded by | Hiroshima: William S. Parsons Paul Tibbets Robert A. Lewis Nagasaki: Charles Sweeney Frederick Ashworth |

| Date | 6 August 1945 9 August 1945 |

| Executed by |

|

| Casualties |

Hiroshima:

Nagasaki:

Total killed:

|

Background

The Pacific War, fought between the Allies and the Japanese Empire, began in 1945 and lasted for four years. The majority of Japanese combat forces engaged in heavy fighting, guaranteeing that the Allied triumph would come at a heavy price. Including both military soldiers killed in action and those injured in action, the United States suffered a total of 1.25 million war casualties during World War II. Between June 1944 and June 1945, the final year of the war, nearly a million people lost their lives. The German Ardennes Offensive in December 1944 caused American fighting fatalities to reach an all-time monthly high of 88,000. President Roosevelt, concerned about the losses incurred, proposed using atomic bombs on Germany as soon as possible, but was informed that.

The United States of America was running low on labor. Tighter deferments were applied to certain categories, such as agricultural laborers, and the possibility of drafting women was discussed. The public was also becoming sick of the war and calling for the return of long-serving soldiers. In the Pacific, the Allies invaded Borneo, took back control of Burma, and made their way back to the Philippines. To lessen the number of Japanese forces still present in Bougainville, New Guinea, and the Philippines, offensives were launched. American forces arrived on Okinawa in April 1945, and fierce battle persisted there until June. Japanese to American casualties decreased during the conflict, from five to one in the Philippines to two to one on Okinawa.

Preparations

Colonel Paul Tibbets oversaw the 509th Composite Group, which was established on December 9, 1944, and brought into service at Wendover Army Air Field in Utah on December 17, 1944. Tibbets was given the task of setting up and leading a combat force to devise a strategy for delivering an atomic weapon to targets in Japan and Germany. The group was classified as a “composite” unit instead of a “bombardment” unit since its flying squadrons had both transport and bomber aircraft. Tibbets chose Wendover over Great Bend, Kansas, and Mountain Home, Idaho, for his training base because of its distant location. Targeting the islands around Tinian and eventually the Japanese home islands, each bombardier executed at least fifty practice drops with inert or conventional explosive pumpkin bombs, until as late as.

The directions of entry and exit with regard to the wind were likewise replicated, as was the actual dropping of atomic bombs. Fearing he would be apprehended and questioned, Tibbets himself was prohibited from flying most sorties over Japan. Operation Centerboard, a code name, was assigned on April 5, 1945. Nobody in the War Department’s Operations Division was authorized to know anything about it, including the officer in charge of allocating it. Operations Centerboard I and II were the codenames given to the first and second bombings, respectively, once they were implemented.

Hiroshima

Hiroshima was an important military and industrial metropolis at the time of the bombing. Several military installations were situated in the vicinity, chief among them being the headquarters of Field Marshal Shunroku Hata’s Second General Army, housed in Hiroshima Castle and responsible for overseeing the defense of the entire southern region of Japan. With over 400,000 men under command, Hata was able to secure the majority of Kyushu, where an Allied assault was duly predicted. A newly established mobile unit called the 224th Division, the 5th Division, and the headquarters of the 59th Army were also in Hiroshima. Units from the 3rd Anti-Aircraft Division, along with five batteries of 70 mm and 80 mm (2.8 and 3.1 inch) anti-aircraft weapons, guarded the city.

Hiroshima served as the Japanese military’s supply and logistics base. The city served as a hub for communications, an important shipping port, and a location for military gatherings. It fueled a sizable armaments sector that produced parts for bombs, handguns, rifles, and boats in addition to planes and boats. There were multiple reinforced concrete buildings in the city center. The region outside the center was clogged with a thick cluster of tiny woodworking shops tucked in between Japanese homes. A few significant manufacturing facilities were located close to the city’s periphery. Many of the industrial buildings were likewise built on timber frames, and the dwellings were made of wood with tile roofs. The entire city was quite vulnerable to fire destruction. The city was the second biggest in.

Events of 7–9 August

Truman declared the employment of the new weapon in a statement following the bombing of Hiroshima. The fact that the German atomic bomb effort had failed and that the US and its allies had “spent two billion dollars on the greatest scientific gamble in history—and won” made him say, “We may be grateful to Providence”. Then Truman issued a warning to Japan, saying, “They may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth, if they do not now accept our terms.” Following this aerial assault will be land and marine forces with combat skills they already know how to use, and in quantities and strength they have never seen before.” This speech was selected for widespread broadcast.

A similar message about Hiroshima was broadcast to Japan every fifteen minutes by the OWI radio station, a 50,000-watt standard wave station on Saipan. The station strongly advised civilians to evacuate major cities and warned that more Japanese cities would suffer a similar fate if the terms of the Potsdam Declaration were not accepted immediately. The Japanese were notified of the devastation of Hiroshima by a single bomb by Radio Japan, which persisted in celebrating Japan’s victory by refusing to give up.

Nagasaki

Because of its extensive industrial activity, which included the manufacture of weapons, ships, military hardware, and other war materials, Nagasaki, one of the biggest seaports in southern Japan, was extremely important during the war. Approximately 90% of the working force and 90% of the city’s industry were employed by the four main firms in the city, which were Mitsubishi Shipyards, Electrical Shipyards, Arms Plant, and Steel and Arms Works. Despite being a significant industrial hub, Nagasaki had avoided firebombings due of its unique topography, which made it challenging to find with AN/APQ-13 radar at night.

Nagasaki was bombarded five times on a modest scale and was not prohibited from being bombed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s 3 July directive, in contrast to the other target cities [121][188]. Conventional high-explosive bombs were thrown on the city on August 1st, during one of these assaults. A couple struck the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, while several others struck the shipyards and docks in the southwest part of the city.In [187] With four batteries of 7 cm (2.8 in) anti-aircraft weapons and two searchlight batteries, the 134th Anti-Aircraft Regiment of the 4th Anti-Aircraft Division was defending the city at the beginning of August.

Plans for more atomic attacks on Japan

After the events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, plans were afoot for more assaults on Japan. Groves projected that another “Fat Man” atomic weapon would be operational on August 19 and that three more would follow in September and October. It would not be possible to obtain a second Little Boy bomb (using U-235) until December 1945. He informed Marshall in a memo dated August 10 that “the next bomb… should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17 or 18 August.” The handwritten note from Marshall that is included in the memo today reads, “It is not to be released over Japan without express authority from the President.” Truman talked about these measures during the cabinet meeting that morning. According to James Forrestal’s interpretation of Truman, “there will.

Surrender of Japan and subsequent occupation

The War Council of Japan continued to insist on its four criteria for capitulation until August 9th. On August 9, at 14:30, the entire cabinet convened and debated capitulation for the most of the day. Anami supported the war’s continuation even though she acknowledged that success was uncertain. At 17:30, the meeting was over and no decisions had been made. In order to report on the meeting’s outcome, Suzuki proceeded to the palace and spoke with Kōichi Kido, Japan’s Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. The emperor would submit to surrender provided kokutai was retained, Kido informed him, adding that the emperor had also consented to hold an imperial meeting. At 18:00, there was a second cabinet meeting. Merely four.

Reportage

The military photographer Yōsuke Yamahata, the writer Higashi, and the artist Yamada arrived in the city on August 10, 1945, the day after the bombing of Nagasaki, with instructions to document the devastation for propaganda purposes. Yamahata captured numerous pictures, which were published in the well-known Japanese newspaper Mainichi Shimbun on August 21. Copies of his photos were confiscated during the subsequent censorship that followed Japan’s surrender and the entrance of American forces, although some recordings have survived.

Newspapers in the United States first published a firsthand account of the incident by former United Press (UP) journalist Leslie Nakashima. He saw that a significant portion of the survivors were still dying from what was eventually identified as radiation poisoning. An edited version of his 27 August UP piece appeared in The New York Times on August 31. There were hardly no mentions of uranium poisoning. According to American scientists, “the atomic bomb will not have any lingering after-effects,” an editor’s comment was added.

Post-attack casualties

An estimated 90,000 to 140,000 people (up to 39 percent of the population) and 60,000 to 80,000 people (up to 32 percent of the population) perished in 1945 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively; however, it is uncertain how many of these people perished instantly from radiation exposure, heat exhaustion, or blast exposure. In a report published by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, it is discussed that 6,882 individuals in Hiroshima and 6,621 individuals in Nagasaki, who were mostly within 2,000 meters (6,600 feet) of the hypocenter, suffered from blast and heat-related injuries but died within 20 to 30 days due to complications that were often exacerbated by acute radiation syndrome (ARS). Many of the persons who were not hurt by the explosion passed away over that period of time as well.

Hibakusha

The term hibakusha (被爆者, pronounced [çiba蜜kɯ̥ʕa] or [çibakʯ̥Ɯʕa]) refers to the bombing survivors and means “explosion-affected people” in Japanese. Approximately 650,000 persons are recognized as hibakusha by the Japanese government. Of them, 113,649 were still alive as of March 31, 2023, primarily in Japan. About 1% of them are recognized by the Japanese government as having radiation-related ailments. The names of the hibakusha who are known to have passed away since the explosions are listed on the memorials at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As of August 2023, the memorials, which are updated annually on the bombing anniversaries, list the names of 535,000 hibakusha—339,227 in Hiroshima and 195,607 in Nagasaki.

Memorials

Typhoon Ida then made landfall on Hiroshima on September 17, 1945. The city was further devastated by the devastation done to the roads, trains, and more than half of the bridges. From 83,000 shortly after the bombing to 146,000 in February 1946, the population grew. With assistance from the federal government and the 1949 Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, the city was rebuilt following the war. Together with donated land that had previously belonged to the national government and been utilized for military operations, it offered financial support for reconstruction. A plan for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park was chosen in 1949. The building that survived the closest to the site of the bombing, the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, was given the honor of being named the Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

Debate over bombings

Both academics and laypeople have debated the part played by the bombs in Japan’s surrender as well as the moral, legal, and military issues surrounding the US’s rationale for them.One side of the debate contends that the bombings forced the Japanese to surrender and avoided the deaths that an invasion of Japan would have brought about. Stimson spoke of averting a million deaths.Without an invasion, the naval blockade may have starved the Japanese into submission, but a lot more Japanese casualties would have followed.

On the other hand, detractors of the bombs have claimed that state terrorism, war crimes, and the intrinsic immorality of atomic weapons all apply to the bombings. Without the attacks, the Japanese might have given up, but it would have just been an unconditional surrender.

Legal considerations

Before the development of air power, the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 were ratified. They deal with standards of behavior during times of war on land and at sea. International humanitarian law was not amended prior to World War II, despite numerous diplomatic attempts to incorporate aerial warfare. The lack of distinct international humanitarian law did not absolve aerial warfare from the rules of war; rather, it only meant that there was a lack of consensus over the appropriate interpretation of those laws.This indicates that no explicit nor implicit customary international humanitarian law forbade the aerial bombing of civilian areas within enemy territory by any of the main belligerents during World War II. The bombs were reviewed by the courts in Ryuichi Shimoda v. in 1963.

Legacy

As of June 30, 1946, the US arsenal included parts for nine atomic bombs, all of which were Fat Man devices that were the same as the one used at Nagasaki. Since the nuclear bombs were handmade, there was still much to be done to make them safer, more dependable, easier to assemble, and easier to store before they could be put into mass production. Additionally, there were a number of performance enhancements that had been advised or suggested but had been made impossible by the demands of wartime advancements. In October 1947, Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, announced a military need for 400 nuclear weapons, despite his criticism of the deployment of atomic bombs as adopting “an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages.